Moon discovered in another solar system (yes: it’s the first exomoon).

Using NASA’s Hubble and Kepler space telescopes, astronomers have uncovered tantalising evidence of what could be the first discovery of a moon orbiting a planet outside our solar system.

This moon candidate, which is 8,000 light-years from Earth in the Cygnus constellation, orbits a gas-giant planet that, in turn, orbits a star called Kepler-1625. Researchers caution that the moon hypothesis is tentative and must be confirmed by follow-up Hubble observations.

“This intriguing finding shows how NASA’s missions work together to uncover incredible mysteries in our cosmos,” said Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator of NASA’s Science Mission Directorate at Headquarters, Washington. “If confirmed, this finding could completely shake up our understanding of how moons are formed and what they can be made of.”

Since moons outside our solar system – known as exomoons – cannot be imaged directly, their presence is inferred when they pass in front of a star, momentarily dimming its light. Such an event is called a transit, and has been used to detect many of the exoplanets catalogued to date.

However, exomoons are harder to detect than exoplanets because they are smaller than their companion planet, and so their transit signal is weaker when plotted on a light curve that measures the duration of the planet crossing and the amount of momentary dimming. Exomoons also shift position with each transit because the moon is orbiting the planet.

In search of exomoons, Alex Teachey and David Kipping, astronomers at Columbia University in New York, analysed data from 284 Kepler-discovered planets that were in comparatively wide orbits, longer than 30 days, around their host star. The researchers found one instance in planet Kepler-1625b, of a transit signature with intriguing anomalies, suggesting the presence of a moon.

“We saw little deviations and wobbles in the light curve that caught our attention,” Kipping said.

Based upon their findings, the team spent 40 hours making observations with Hubble to study the planet intensively – also using the transit method – obtaining more precise data on the dips of light. Scientists monitored the planet before and during its 19-hour transit across the face of the star. After the transit ended, Hubble detected a second, and much smaller, decrease in the star’s brightness approximately 3.5 hours later. This small decrease is consistent with a gravitationally-bound moon trailing the planet, much like a dog following after its owner. Unfortunately, the scheduled Hubble observations ended before the complete transit of the candidate moon could be measured and its existence confirmed.

In addition to this dip in light, Hubble provided supporting evidence for the moon hypothesis by finding the planet transit occurring more than an hour earlier than predicted. This is consistent with a planet and moon orbiting a common centre of gravity that would cause the planet to wobble from its predicted location, much the way Earth wobbles as our Moon orbits it.

The researchers note the planetary wobble could be caused by the gravitational pull of a hypothetical second planet in the system, rather than a moon. While Kepler has not detected a second planet in the system, it could be that the planet is there, but not detectable using Kepler’s techniques.

“A companion moon is the simplest and most natural explanation for the second dip in the light curve and the orbit-timing deviation,” Kipping explained. “It was definitely a shocking moment to see that Hubble light curve, my heart started beating a little faster as I kept looking at that signature. But we knew our job was to keep a level head and essentially assume it was bogus, testing every conceivable way in which the data could be tricking us.”

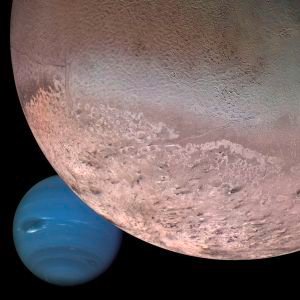

In a paper published in the journal Science Advances, the scientists report the candidate moon is unusually large – potentially comparable to Neptune. Such large moons do not exist in our own solar system. The researchers say this may yield new insights into the development of planetary systems and may cause experts to revisit theories of how moons form around planets.

The moon candidate is estimated to be only 1.5 percent the mass of its companion planet, and the planet is estimated to be several times the mass of Jupiter. This mass-ratio is similar to the one between Earth and the Moon. In the case of the Earth-Moon system and the Pluto-Charon system, the moons are thought to be created through dust leftover after rocky planetary collisions. However, Kepler-1625b and its possible satellite are gaseous and not rocky, so the moon may have formed through a different process.

Researchers note that if this is indeed a moon, both it and its host planet lie within their star’s habitable zone, where moderate temperatures allow for the existence of liquid water on any solid planetary surface. However, both bodies are considered to be gaseous and, therefore, unsuitable for life as we know it.

Future searches for exomoons, in general, will target Jupiter-size planets that are farther from their star than Earth is from the Sun. The ideal candidate planets hosting moons are in wide orbits, with long and infrequent transit times. In this search, a moon would have been among the easiest to detect because of its large size. Currently, there are just a handful of such planets in the Kepler database. Whether future observations confirm the existence of the Kepler-1625b moon, NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope will be used to find candidate moons around other planets, with much greater detail than Kepler.

<iframe width=”450″ height=”253″ src=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/Q8QFyOaTdZk” frameborder=”0″ allow=”autoplay; encrypted-media” allowfullscreen></iframe>